Thinking back on his days growing up on Quarry Street, Laventille, Everard Romany, co-creator of Rapso, recalls hanging on the block with his friends. It was a busy street, a close-knit community where everyone knew everyone and everyone looked out for each other.

Romany knew everyone on the street, including a young Brother Resistance, known then by his birth name Roy Lewis, but it wasn’t until their teens that they became friends.

“His father was a disciplined person,” Romany recalls.

“His father was a Bajan and he had a vision for his two sons. He made sure that they go to school and when they come from school they do their homework and they don’t play with us. So Resistance, for the first 15/16 years we had no physical contact. His father wanted the best for his children,” says Romany who lived about 25 meters from him.

He said at 18, Resistance was old enough to defy his father and hung out on the block where he, Romany and others would smoke, beat drums and make music.

Describing Resistance as an educator and a visionary, Romany said he was possessed with poetry and music and suggested they start doing poetry together.

“It was myself, Resistance, Wayne Blackman who we called Moopsman and Curtis “Slinger” Hughes, the four horsemen. This is how it started, it started on the hill,” Romany recalled.

At first, they called what they did poetry because that is what the three main poets of the day —Lancelot Layne, Abdul Malik and Lasana Kwesi — called their art.

The young warriors, influenced by their history and the Black Power Movement, sought a name to define their style of art and differentiate themselves from the mainstream poets. They called their art Rapso.

Romany, who went by the name Brother Shortman, says he and Brother Resistance have differed on the origins of the word Rapso.

“Me and Resistance met in 2004 and we were talking and I ask him about the word Rapso, he said people used to ask how we could rap so but in the 70s the word wasn’t in the air, Rapso wasn’t a word that was used. The only two words closely related to Rapso was Rhapsody in Blue, a movie, and H Rap Brown, a Black Panther freedom fighter. I believe we got the word from these remnants of words. Somewhere in that space I could never ever in my life explain how and when and what time we come up with the word,” he told Loop during an interview on Thursday.

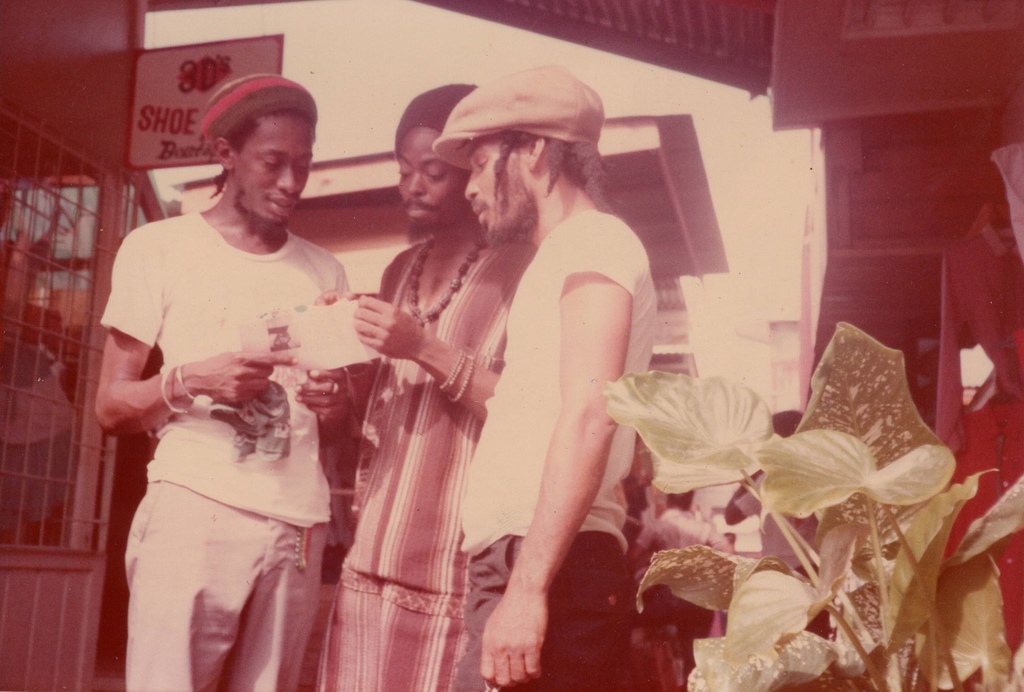

Everard Romany and Brother Resistance. Photo courtesy Lars Hanssen

Around 1972/73 the four men formed The Network Riddum band and the Cold Concrete Network Youth Movement. They rehearsed in a bamboo shed on a piece of land on Quarry St where Romany’s family once squatted. The house had fallen to ruins, he said and he constructed a bamboo shed to do his leatherwork.

Romany, who dropped out of school in Form Two after his father left the family and migrated to the United States, followed in his dad’s artisan footsteps, making bags and sandals among other items to sell to support his mother and siblings.

For almost 10 years the Network Riddum Band performed mainly for Trade Unions who hired them for various events because of their songs which resonated with the working class.

Romany said Hughes sang the first rapso hit “Wuk and Dead” an unrecorded song that echoed through the ghettoes with the words emblazoned on walls.

In 1981, however, they got their big breakthrough with the release of their first album, a 45 record called “Busting Out” with two songs “Squatter’s Chant” and “Dancing Shoes”.

The album was recorded at KH Records in Sealots and prior to recording, Ras Shorty I, the father of soca, provided a lot of direction and guidance to the young artistes.

Romany said they used professional studio musicians on the first album since their band was not yet ready. The group of youngsters they had curated from the area, some as young as 13, were now learning to play instruments that he and Resistance bought for them.

The original musicians of Network Riddum Band were Norbert “Mickey” Moore, drummer and bass guitarist; Steve Jemmot, tenor pannist and arranger; Wayne “Bongo” Haynes, African drummer; Sister Irma Williams, the first female Rapso artiste; Kurt the “Faithy” DeFreitas, double second pannist; Derek Benny Jones, African drummer and double second pannist; Clyde Jones, African drummer and Rapso recording artist; Cyril “Stou” Jack, bass guitarist; Neal “ Tripper” McConney, lead guitarist; Oba Bop, drummer; Dawn “Black Pearl” Peters, congas; Anthony Humphrey, percussionist; Peter Joseph Elie, manager and Ralph LeGendre ”Blockmaster”, the Rapso DJ.

Romany said the late Ja Jah Oga Onilu, who introduced the Orisha vibe into Andre Tanker’s band, taught some of the musicians the art of making and playing the drum.

The group, Romany said, was one big family.

“Togetherness was the essence of the struggle. The family that prays together stays together. We started holding hands in a circle and the first time we experimented with spirituality there were struggles in the yard, but being persistent the forces left us and we got peace. We were revolutionary in what we did, we became vegetarians, we turned away from religion but we believed in spirituality. It takes a village to raise a child and the foundation of Rapso is building a family and that is the foundation,” said the 69-year-old who is deeply spiritual.

Busting Out, as its name declared, was an instant success but the band struggled with the authorities.

The Port-of-Spain city corporation evicted them from the land and Romany and Resistance ended up in court as they fought to keep the spot.

After bargaining with Cuthbert Joseph, the then Member of Parliament for the area, they got a place on Observatory Street in Port-of-Spain.

Having inherited business acumen from his father who was a business man, Romany, who also managed five contracts under the Government’s Special Works Projects, an early version of CEPEP, strategised to ensure they could support themselves to keep doing the music as self-sustenance was one of their pillars.

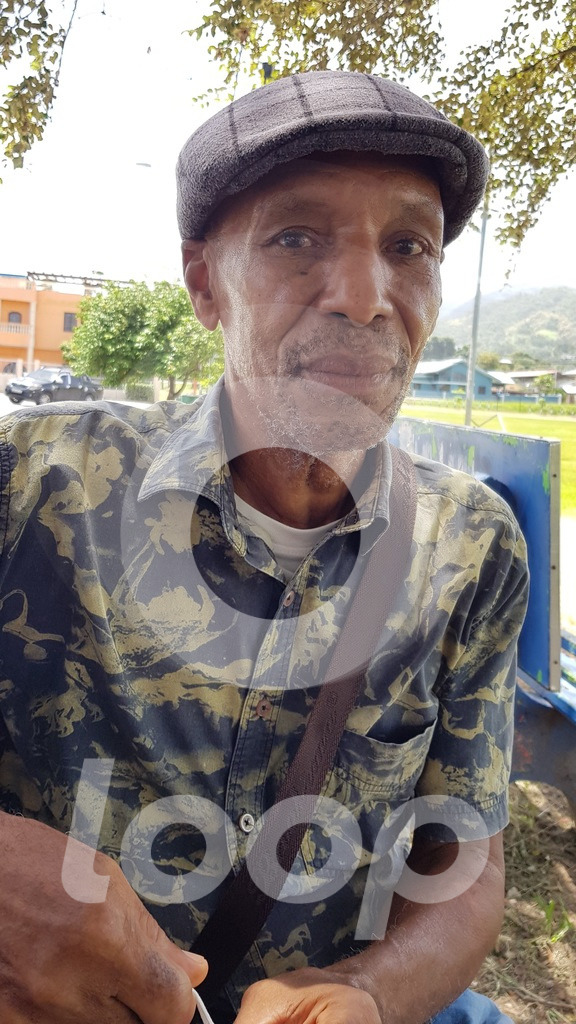

Everard Romany known today as Rapso Rebel. Photo by Laura Dowrich-Phillips

When they received royalties from the album — as much as $65,000 in one instance over one six-month period — thanks to their membership with the Performance Rights Society, they realised they could continue making money if they did more albums.

They borrowed money from several banks and started a company called Network Publishing of which Romany was the Director and Resistance the General Secretary. Under the publishing company, they recorded their music and that of Karega Mandela and Clyde Jones, calypsonian African Teller from Grenada and Merchant’s “Shellyann” and “Come Let Us Build a Nation Together”.

They also operated two stores, one on Observatory Street, the other, Uprising, in the Drag Mall. They sold leather goods that Romany made, ancient African musical instruments from Ja Jah and, in the mall, also sold albums from calypsonians who found space to lime on occasion.

“We were flying but we were innocent, we didn’t understand the music business, it is a money monster, it loves to take money so at a certain time we were taking money from our businesses that were successful and putting it back into the music. This is something we had to do.”

Between 1981 and 84, the band produced five albums, the last one, Rapso Xplosion had six tracks and featured the vocals of Karega Mandela for the first time. Romany described Mandela as a focused and determined youth from Blanchisseuse who worked hard to develop his musical talents.

He credited Mandela for filling the void and standing with Resistance after his departure from the band. Brother ResistanceIn 1984, suffering from a dread tabanca after his first wife left him and subsequent drug use, Romany left the band.

Brother ResistanceIn 1984, suffering from a dread tabanca after his first wife left him and subsequent drug use, Romany left the band.

He said he didn’t want to taint the band or Rapso and as such, chose to withdraw completely.

After getting off drugs in 1989, he met a Swedish woman who was looking for directions with her friends in Port-of-Spain and ended up migrating to the Scandinavian country where he lived for 10 years.

Thanks to a group there called Soca Rebels who found him, Romany made a comeback in 2005 performing with his band House of Rapsoul.

He returned to Trinidad and has been back and forth since.

The reclusive father of two, now known as Rapso Rebel, has written a book called Word Catcher and is still making music, among them songs such as “Stories”, “Oh Laventille” and “Aum Shanti”.

He had plans in the works for a book on The Network Riddum Band and had reached out to the surviving foundation members including Resistance to write their own chapters.

He said when people ask him if he is not mad that Resistance is the one who gets all the credit for Rapso, Romany he could never be mad because he loves Resistance and he is proud that he kept the music going all these years.

In fact, it was only a few months ago he had the opportunity to meet up with Resistance, hug him and tell him how much he loved him.

To those mourning the loss of his friend he said: “The messenger has left us but the message will live on.”